Underground ︎︎︎

As city dwellers, we tend to overlook the fact that the urban landscape is composed of more than the material architecture in our lines of vision. Not only have natural topography and elements shaped the design of private and public spaces, but the underground landscapes of our cities have a crucial relationship and a constant dialogue with the structures we are able to see at plain sight.

London as a city sits on a basin of very particular geological characteristics. Different to many other parts of England, the soil composition of London consists of a very thick layer of what is called London Clay.

London Clay is a stiff, bluish clay that becomes brown when weathered and oxidized. It is a marine geological formation well known for its fossil content, which is indicative of warm, probably tropical climatic conditions that prevailed in western Europe during the Eocene.

Its characteristics create a soft yet stable environment ideal for tunnelling, which facilitated the early development of the London Underground. But this is also the reason why London didn’t have many skyscraper buildings until more recently. The London Clay means that foundation piles needed to be very deep for tall buildings which was often too costly for developers. It wasn’t until the development of plunge piles, which function as rafts embedded in the clay, that taller buildings began to be built in London.

London Clay is highly susceptible to volumetric changes due to its moisture content. Although impermeable, it can be hugely affected by long periods of extreme weather conditions.

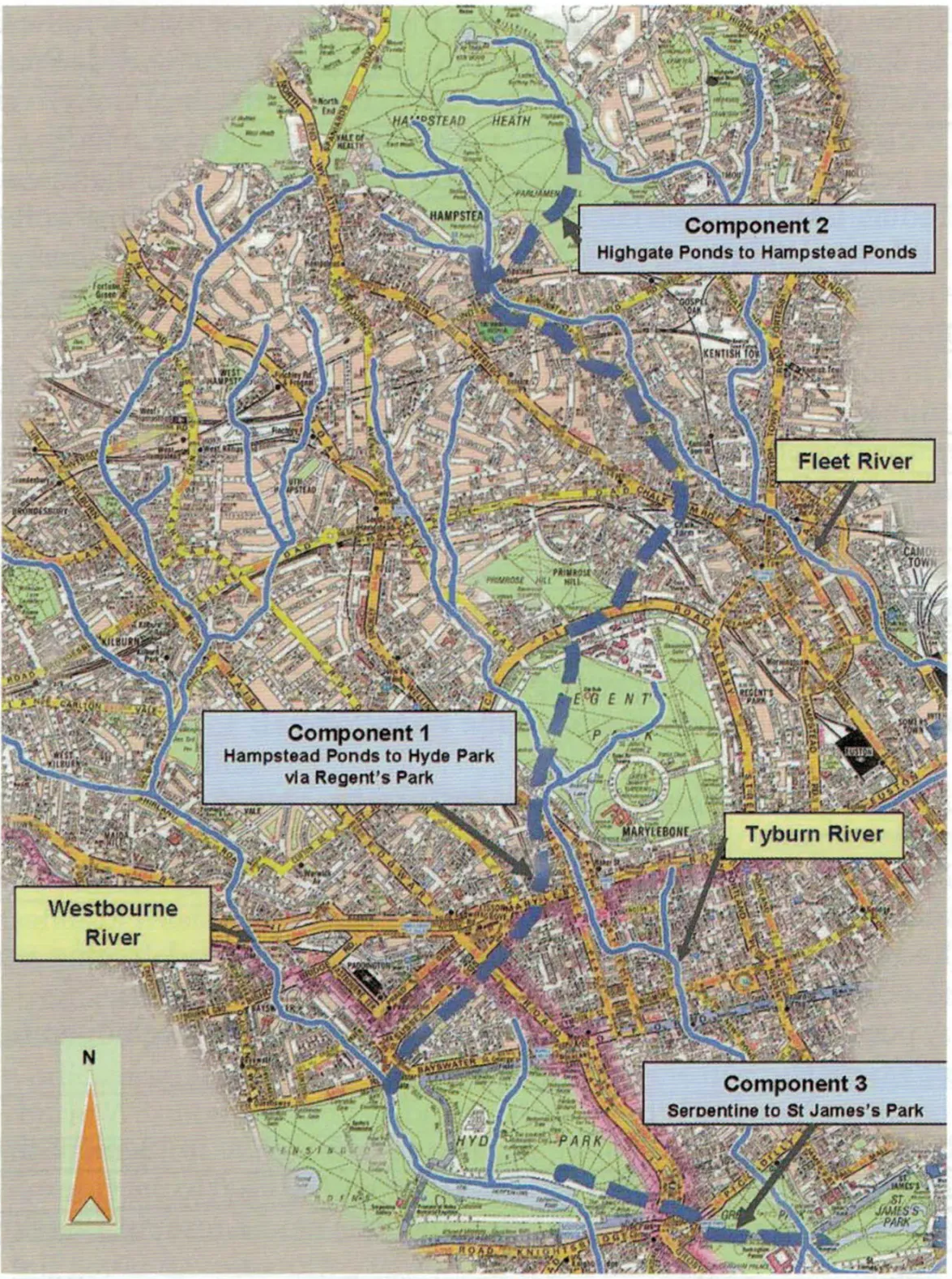

Another aspect of the London underground landscape is its hidden hydrology. In its early life, the Thames was fed by multiple tributaries that ran through the city. Over time these rivers have been tubed and eventually most became part of London’s sewage system.

In our area of study, especially because of its vicinity to Hampstead Heath, a few of the main tributaries were born and ran through the land that is now occupied by some of the Estates in question.

The river Tyburn sprang south of Hampstead Heath and ran through the Chalcots Estate and Regents Park south towards the Thames. A couple of the many branches that sprang to feed into the river Westbourne seem to have run through what is now the Alexandra and Ainsworth Estate.

Once clear and sparkling, the Tyburn ran along what is now Marylebone Road northwards. After being used to form the pond in Regent’s Park, it was progressively covered over. As developers such as the Chalcots and Eyre Estates built houses in the area, the Tyburn began to disappear from view completely. By the 1830s new housing between Swiss Cottage and Hampstead saw the river covered and forced underground. . In its underground form, the Tyburn was incorporated into the surface water drainage network, but by the 1860s it had become a sewer.

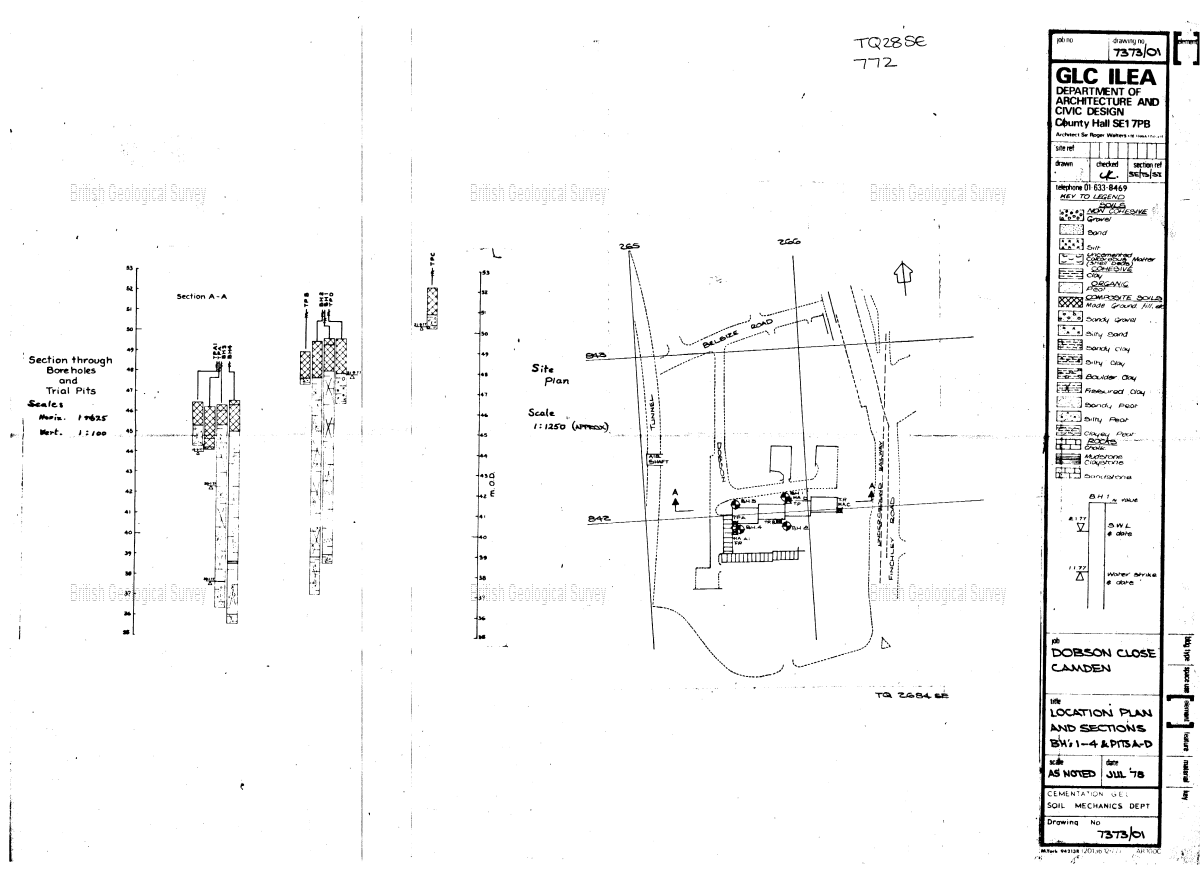

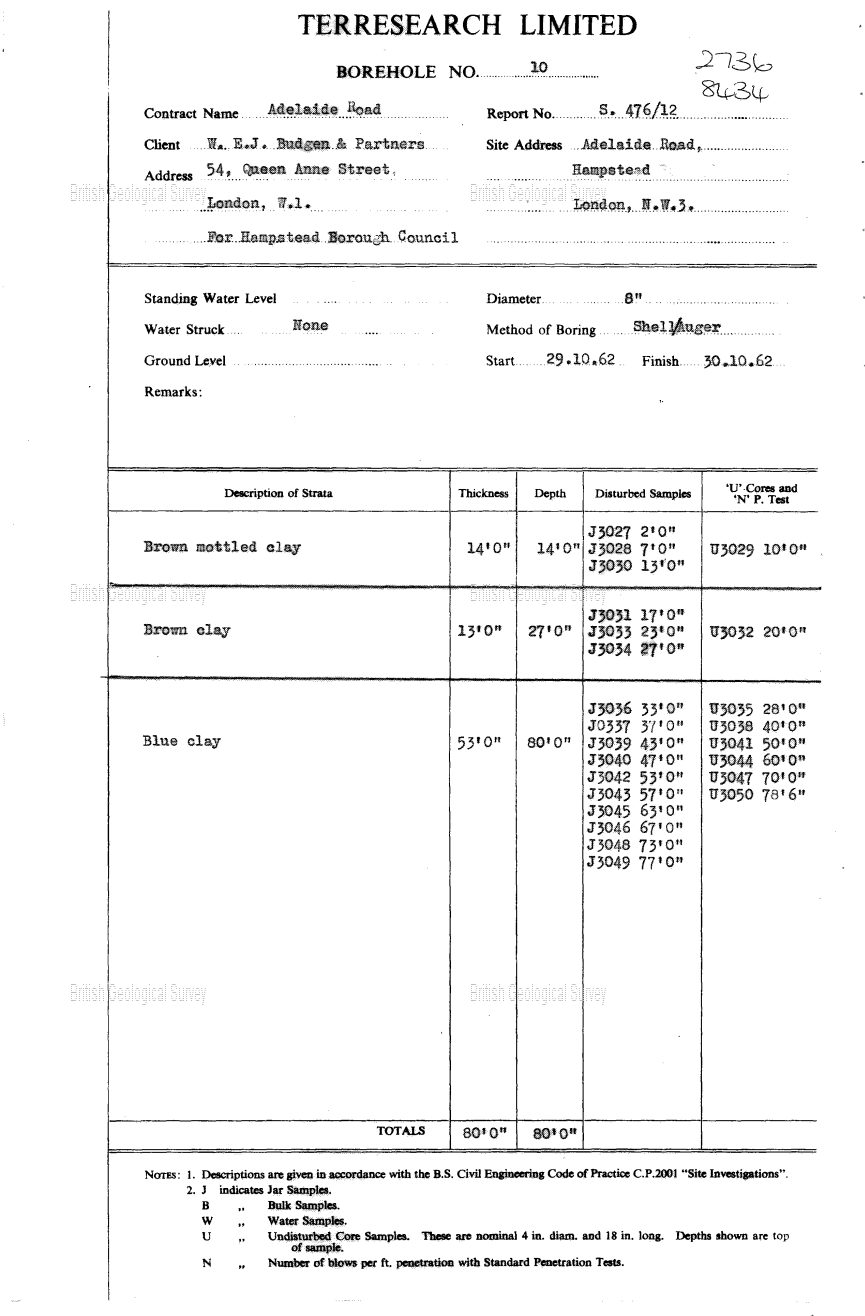

To access the layers of the underground landscape, architects and engineers use boreholes and wells. The British Geological Survey (BGS) serves as a reference to specialists in the initial steps of the soil studies needed for building. Using the BGS, we have found several sources of data in our area of study.

- A borehole from 1978 on Dobson Close on Hilgrove Estate

- A series of boreholes from 1962 at the east end of Chalcots Estate

- A water well borehole from 2004 at the Swiss Cottage open space near the Leisure Center

This last water well, according to a garden caretaker in the location, used to feed the water for the large rectangular fountain in Swiss Cottage Open Space. This fountain, together with the green areas around it was identified as one of the most loved spaces in the neighbourhood by residents of Hilgrove and Chalcots estate during a workshop conducted by the Open City team.

BGS Borehole Records